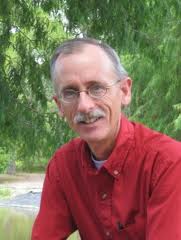

Brian Yansky writes YA novels and teaches writing at Austin Community College. In his books he tells the stories of teenaged boys. I first met Brian at the 2012Austin SCBWI Annual Conference. Since then I’ve been lucky enough to get to know him a little better and read two of his sci-fi novels, Alien Invasion and Other Inconveniences, and Homicidal Aliens and Other Disappointments. In addition to his full-time jobs writing novels and teaching at ACC, Brian sometimes teaches short format classes for The Writers’ League of Texas. Not to gush, but I can tell you from firsthand experience it’s worth the money to take one of these (usually half day) courses, because he teaches as well as he writes.

In many ways, Brian is the perfect example of a writer who is daring to buck some of the YA publishing trends I’ve been talking about in my ongoing series on the topic of teen, male aliteracy.

I posted a review of Homicidal Aliens on my personal blog late last week.

Here’s Part One of my recent email interview with him:

BPW: In Homicidal Aliens, just as in Alien Invasion before that, your first person narrator Jesse sounds exactly like who he is, a male teenager. Your language has a genuine plainness to it that’s highly effective. It’s also in keeping with what Andy Sherrod identifies as one of the defining characteristics of a boy book: the intense emotions the characters are feeling are undercut by your narrative voice. Is there a “real” Jesse whose voice you borrowed from? Either way, can you talk about developing your distinctly teen, male voice?

BY: First, thanks for saying that. I do want every character to have a distinct voice, and I struggle to make my characters sound the age they are. It may help that I suffer from arrested development, and a part of me still sometimes reacts like a teenage boy: “I have to do that? You mean I have to do that now?” So I do get in touch with my inner teenager when I write my young adult novels. I suppose the voice is some mix of my memories of myself and my friends at that age, my imagination, and my observation of teenagers – both in real life (one of the benefits of teaching at Austin Community College) and in the novels I read, movies and TV I see, songs I hear. The way a voice comes is a bit of a mystery, but as I’m building a character – adding specifics about how a character sees his world and what he does in it – the voice becomes clearer and clearer in my mind.

BPW: You successfully write for a teen audience. Do you have teen beta readers?

BY: I don’t.

BPW: Is it because you choose not to? Or is it more a matter of limited access?

BY: There are probably a few writers who do have teen readers, but none of my writer buddies do. Every writer is different though. I just do my best to be true to the character. Then I have a critique group, who all write YA and Middle Grade, read my work. Then my agent, who sells mostly YA and MG. Then my editor at Candlewick. So if there are places where the voice seems inauthentic, I get feedback. But, honestly, I rely mostly on my ear and, as I said before, a combination of observation, imagination, and memory.

Look for the rest of my conversation with YA novelist Brian Yansky in two weeks, and find out how discovering reading as a teenager changed his life.