Below is part one of my email conversation with Central Texas’ own expert on teen, male aliteracy, Andy Sherrod.

BPW: I first met you when you gave your Boy Book Seminar at the Brazos Valley Chapter of the SCBWI. I still use the little ruler you handed out. It came in handy just the other night to describe the difference between boy books and girl books to the guy who installed my floors. Thanks for making such a clearly understandable tool.

AS: I’m pleased you still have that ruler. I designed it to be a book mark for adults to use as they evaluate books for young readers to see how those books “measure up.”

Andy Sherrod’s Ruler

BPW: Can you start by talking about aliteracy vs. illiteracy? And then define the term ‘boy book’ for those who haven’t attended your lecture on the subject.

AS: I first ran across the termaliteracy when I was doing research for my thesis and I latched on to it. It is exceptionally descriptive of the attitude some people have toward reading. An aliterate reader is one who CAN read without difficulty but chooses not to engage in active literacy in lieu of other activities. Illiterate readers, of course, either can’t read or do so with great difficulty.

I have found that many people shy away from using the terms ‘boy book’ and ‘girl book.’ I can understand that to some extent. If a boy likes a book labeled a ‘girl book’ then he risks ridicule. The point is that males and females are different and so are their interests (I’m speaking broadly here). Educators will tell you that it is mostly boys who are aliterate and cite various reasons as to why that is. In deciding my thesis topic I wanted to explore this condition and see if there were identifiable literary components which attracted male readers, the knowledge of which would bring educators (and parents) one step closer to engaging boys in active literacy. There are, indeed,identifiable literary components which attract the attention of most male readers! When those literary components are compiled into one book, it becomes a boy book.

[I talked about Andy’s list of components in my my last post.]

BPW: The topic of male teen aliteracy has been a focus of yours for years now, since graduate school. Are more boys reading now than when you first started your inquiry? Specifically, are any more boys reading prose fiction? Can you elaborate on why you think this has or hasn’t changed?

AS: I am a writer and promoter of reading. The arena in which I earn my living, however, is far removed from the literary world. Upon reflecting on your question I wrote several of my friends who do interact with children and reading on a day-to-day basis and, though anecdotal, there seems to have been a definite shift in the last few years. The publishing industry made a concerted effort to push more boy books and the boys have responded, not so much in the number of boys engaged in voluntary reading but in their choice of reading material. Whereas boys used to be attracted to adventure-type books like Gary Paulsen’sHatchet (and many still are, by the way) they are now reading more science fiction and graphic novels. Though I am not completely up to date on current science fiction, that which I have read still contains the literary components of a good boy book.

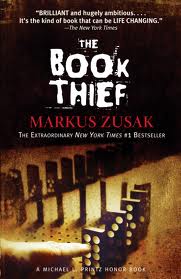

One of the Quintessential Boy Books

BPW: We’ve established that your interest in aliteracy goes pretty far back. It was the topic of your critical master’s thesis. Do I remember correctly thatVermont College of Fine Arts requires a creative thesis as well? If so, was yours a boy book?

AS: VCFA does, indeed, require a creative thesis. You ask if my book is for boys. It has all the literary components of a boy book, so I assume that it is. But I always encourage writers to write from the passion that is deep inside them. Otherwise the story comes across as superficial or forced. As for my creative thesis; it’s historical fiction based on the story of Gideon found in the book of Judges. In one scene Gideon commands his eldest son, Jether, to execute the vanquished princes of Midean. We are told that Jether “…did not draw his sword, because he was only a boy and he was afraid.” I wondered why he was afraid, so I wrote his story.